Many of us do. Enjoy a good one, that is. Why is this? Because, I suppose, we are as humans to a greater or lesser degree empathetic souls. This empathy is engendered largely perhaps by influences in childhood, whether by formal religious teaching, other moral or ethical inculcation or simply by parental example.

For some, a personal values system might be pretty much fully formed upon marrying and assuming the responsibility of parenthood; for others character development might be a slowly evolving process throughout life.

But the fact remains: depending on our particular sensitivity-quotient, we respond to – perhaps ‘enjoy’ isn’t quite the right word – tragedy in literature. We feel that unless we’ve been made to weep a little, or at least be stricken by a lump in the throat by a particularly sad story, it hasn’t really quite worked for us. We feel vaguely cheated if we haven’t been moved.

Of course this need, if such it is, only works in some genres. Most of all, it goes without saying, it applies to romantic literature, which is intrinsically emotional anyway; but it’s a desirable ingredient of ‘issues’-based fiction or non-fiction too. It happens less in genres like fantasy, where characters are paper-thin and either wholly evilly black or angelically white, and the former get their come-uppance whilst the latter, satisfyingly, triumph in the end. (But then, hey, this is the formula that sells books. Especially if books are in a ‘series’, with total predictability.)

In other genres, empathy often isn’t a requirement anyway. Like crime, which almost always means murder (when did you last read a gripping thriller about a burglary?), the ramifications of which are completely suborned to the involvement of the case solving or the thrilling capture/killing of the (often serial) killer.

For myself, I confess that I do like (again, using the word advisedly) books that move me to sympathy; books about real people suffering, or sometimes threatened with, real tragedies. As in, for example, Chris Cleave’s Gold or Jojo Moye’s Me Before You. My two most recent reads have told, through the stories of individual families, the tragedies of entire peoples caught up in the depressingly and seemingly intractable ‘conflict’ (to grossly understate) between Israel and Palestine.

In Mornings in Jenin Susan Abulhawa tells a harrowing story of displacement, exile and repression. I’m simply not qualified to judge whether this was a fair and balanced telling (Ms Abulhawa is an Arab) of the Palestinian’s forcible ejection from their homeland to make way for the state of Israel. All I know is that I was deeply moved by the personal tragedies of the individuals involved; thought it a plea for reconciliation and peaceful coexistence if ever there was one.

By the same token my latest read, the iconic diary of Ann Frank, in its fullest version called The Diary of a Young Girl is absolutely heartbreaking too, because you know only too well the dreadful fate awaiting bright, intelligent, full-of-the-concerns-of-adolescents-everywhere Ann, who speaks so movingly of the privations of hiding and increasing fear of discovery, and who, like a fluttering butterfly in a clenched fist, so longs for freedom. (Which isn’t in any way to lessen the equal evil visited upon the millions of others less bright or intelligent victims, of course.)

Like Mornings in Jenin, Ann’s so, so poignant and tragic journal is hardly pleasant reading – but then neither should it be. Sometimes literature should make us rage; should make us cry. I try not to deny sadness in my own writing. The unheroic, unremarkable tragedy that so often touches ordinary lives should be chronicled too.

There is both near- and actual tragedy in the latest instalment of Wishing for the Better. Here it is.

Wishing for the Better/6

Then, finally, in the spring of 1965, it happened. As usual, it wasn’t a case of me sweeping someone off her feet after a self-confident chase; rather one of someone taking a bit of a fancy to me, inexplicably, and letting it be known through friends. I’ve never understood what she saw in me, remembering the pompous immature idiot I was then. Steph was short (even shorter than me, and I’m only 5ft 4), brunette, attractive, wore dark-framed glasses and exuded a slight air of scholarly street-wisdom. A sophisticated woman! She was slightly older than me, already turned twenty-two, and was in the final year of a computer programming course at the college of technology. Being reasonably assured of success, it wasn’t too difficult, even for me, to make a nervous move. In a breathtakingly short time my virginity was lost and we were a pair. I soon forsook poor old Ted and moved in with Steph, although she was sharing a (proper) flat with another girl. Students were pretty easy going about such arrangements then; I suppose they still are. I was bowled over by this new situation. Apart from the grown-upness of the physical relationship, Steph was just amazing; a far bigger prize than I could ever have imagined winning. She was from a lower middle class background. Her dad was a service manager in an electronics shop and her parents actually owned their own detached house.

Also, very significantly for my development of attitudes and outlook, her parents were Guardian reading socialists, and so was Steph. This was a tremendous revelation. I’d read George Orwell without really understanding the politics, but here was someone, my lover, who could educate me in a philosophy that I was already primed to accept, through religiosity and the college experience, but couldn’t yet articulate. It began to crystallise the gradual evolution of my outlook on life. It was self-discovery. I really do owe Steph an awful lot; she has been one of the major opinion influencers of my life.

For the rest of that term we lived life on a high, a heady mix of love, discussion and music, mainly the beautiful idealistic ‘protest’ music of Joan Baez or the melancholic poetry of Leonard Cohen. As students on a crusade to build a better world (if only in impassioned debate), we of course loved him rather than loathed him (as many people do), and found his words highly meaningful. Social life got a little more exciting. We got involved in the annual Pram Race, which was part of Rag Week. This was a marathon race from London to Leicester, dressed in silly costume and running, pushing a pram. There would be teams of runners from the various college courses, travelling in buses that drove slowly behind the runners. Not being experienced marathon runners, each participant would be replaced after a spell by someone else from the coach, the replacee rejoining the coach for a rest.

It was run during the night, presumably because the roads were almost empty then. A series of slow moving busses would have caused serious obstruction on the A5 during the day. The typo and graphic design courses had put up a combined team, and on the Saturday before the event we travelled on our hired coach to the capital. It was my first visit to The Smoke apart from a holiday with an aunt when I was eighteen, so that was an adventure in itself. First there was some serious drinking to do (insofar as I ever did serious drinking) in a pub by the Thames in Wapping. Then we made our way to Regents Park, the assembly point for the race. At midnight we began. Given that we were quite a large party, the amount of time each of us spent actually running wasn’t all that great. So for those who were couples, most of the time was spent on the coach smooching. The actual changeover process was potentially hazardous. A replacement runner would stand by the open door of the coach grasping the vertical chrome bar. The coach would slow to walking pace, but not stop, the runner would carefully leap off trying to avoid falling over, run to take over the pram in front, and the other runner would join the coach.

I remember being very stupid. I was standing waiting at the door for my turn to run. Holding the bar, I casually swung out of the doorway, out of the driver’s view. The coach braked sharply and I swung back in. The white-faced, furious driver delivered a blast of very creative and violent invective; he thought I’d fallen under the front of the coach. He addressed the team generally: ‘For Christ’s sake you lot; be bloody careful!’ On reflection, I don’t think the word was ‘bloody’. He was quite right of course. Poor man, having to constantly concentrate so hard, he probably wasn’t enjoying the experience as much as us.

We arrived, tired but happy, in Leicester at 9.30, were home at 10, and went straight to bed. It wasn’t until the following day that we heard the dreadful news. Someone had indeed fallen in front of another coach and been killed. What a terrible price to pay for innocent fun. Imagine how the poor driver of that coach must have felt, not to mention the family of the student. The tragedy caused an enormous furore, and the Students Union never ran the event again.

Soon the end of term arrived, and the end of Steph’s course. What to do now? She had done some work experience with a government establishment in Middlesex during her course, and now had a firm job offer from it that was too good to refuse. We’d been together just three months but were already talking about marriage. When should we time it for? Considerations like how we’d deal with separation if she was working in Middlesex and I was still in Leicester were temporarily brushed under the carpet. For some reason, and I forget what our rationale was now, it seemed that the only logical time would be very soon. Like in a fortnight’s time, before she began her job.

So I went home and told my parents the glad tidings that I was getting married. Dad looked mildly pleased; Mum was delighted. Then I added the second bit: ‘. . . in a fortnight’. Mum modified her reaction to ‘fairly pleased’. Dad looked aghast. They’d assumed the obvious thing: we were having to. I assured them that wasn’t the case. As far as we knew, it wasn’t. I said that it was just for logistical reasons (although I probably didn’t use that word) and anyway, it wasn’t precipitous (I don’t think I used that one either); we felt that we known each other for years. How many young lovers in the history of mankind have said that?

I don’t think they quite bought my carefully reasoned arguments. Eventually Mum said, ‘well, if you don’t you’ll only go and live together’. I refrained from comment. So that was that; it was arranged. I returned to Leicester. Meanwhile Steph had been on the same mission to her parents who, being more liberal minded than mine, had taken it in their stride. Obviously, a church wedding was out of the question on such a short time scale – not that we would have wanted one anyway – and it was arranged at the register office of Steph’s hometown in Nottinghamshire, with the reception to follow at her parents’.

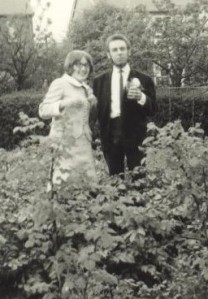

So on the Friday before the big day I travelled to Stamford again so as to arrive with my parents, Derek and Gerald and his wife. I suppose there was an element of respectability there: it couldn’t appear as if Steph and I were already cohabiting. There were a few members of Steph’s family, and friend Ivan the Terrible doing the photographs. I looked dashing in a blue corduroy jacket, black drainpipe trousers, white shirt and black leather tie (I had abandoned suits by now, as befitted a radical student, and didn’t possess one) and Steph looked lovely in a new suit bought her by her mum. It was all about as low key as you can get. Steph’s dad drove us to the register office in his firm’s Ford Anglia estate specially cleaned for the occasion, the brief deed was done, photos were taken outside the office, we returned in convoy to the house, food was consumed, toasts were proposed and I made a dreadful red-faced stuttering groom’s speech. Then we trooped outside and I, with tremendous Beatles-inspired wit, suggested more photos of the happy couple standing in the middle of the vegetable patch, knee-deep in main crop potatoes. Ivan thought that hilarious and was happy to oblige; Dad was less sure about it.

Then it was the Going Away: another trip in convoy to Nottingham train station, good luck messages in lipstick scrawled on our borrowed suitcases by Ivan, and we were waved off. It was hardly an exotic honeymoon either (not Barbados or anything), just a week in Somerset at –yes, you’ve guessed it – Minehead. But not, decidedly not, Stalag Luft Butlins. Apart from my knowledge of the kitchens, that sort of holiday would have been just too passé for us. We stayed at a pleasant little hotel that was affordable because our present from my new in-laws had been honeymoon money.

Back home in the real world, there was the question of work. Steph began her job in Middlesex and I went with her to work for my second summer holiday job at a Shell country club nearby. While we were there she found she was pregnant, which rather upset our plans. She would have to leave the job she’d so recently started and return to Leicester. She got a short term job in the city and we awaited the arrival of our child.

Then I did another of my silly things and bought another vehicle: an Austin A30 van and, again, a load of rubbish. I suppose we felt that a vehicle would be a Good Thing to have when the baby came. Meanwhile, because I didn’t need transport to get to college, and Steph didn’t drive, it would be kept off-road. So I bought it and drove it home to keep in the yard at the back of the flat.

The autumn of 1965 passed, Christmas came and went and the year turned. In the Spring Steph finished her job. She had decided on a home birth (which was a fairly common option then) at her parents. As her time got very near, to be sure of being in the right place she went home to her mum leaving me, a typical useless young male (I’ve often thought we’re the inferior gender) fretting at Melrose Street. The worry came to a head on the Friday evening after she’d gone, and I did something very rash. Our landlord had been grumbling about the van parked in the yard being in his way, and I was desperate to see Steph, so I decided to drive to Nottinghamshire. The van could be parked up there until I put it officially on the road. I should have weighed the probability of Sod’s Law operating that evening, but didn’t. I drove the van out of our yard and had gone no further than twenty metres down the street, belching clouds of blue smoke from the clapped out engine, when a motor-bike overtook and pulled up in front of me. It bore on its rear the legend ‘Police’. It had appeared from nowhere, attracted I suppose by my spectacular display.

I stopped. The policeman got off his machine, set it on its rest and approached with the slow calm deliberation of his profession. He peered in at me through the smoke.

‘Smoking a bit aren’t we Sir?’

‘Er, yes’, I stuttered.

His gaze took in the windscreen, innocent of a tax disc.

‘Are we taxed then?’ I thought it was strange the way he kept addressing me in the plural.

‘Not at the moment’, I said weakly, ‘actually I’m just moving the van’.

He smiled pleasantly, reaching for his notebook.

‘Right. Can I have your full name, please?’

With a feeling of awful inevitability, I gave full details.

‘Right’, he repeated when everything was written down, ‘Can you take your documents into the station within ten days. Goodnight then’.

And with that he returned to his bike and rode away. I sat in the van and considered my situation. Well, I thought, I’m nicked now. Might as well be hung for a sheep as a lamb. So I started the engine, looked carefully around for any sign of the policeman and carried on. When I got to Steph’s parents, she was showing no signs of imminent labour and the weekend was spent worrying about other matters. On the Saturday morning I taxed and got an insurance cover note for the van, with glum thoughts that included the words ‘stable’, ‘door’, ‘horse’ and ‘bolted’. Back in Leicester the next week, with a sinking feeling I presented my documents to the police. They were not slow to notice the discrepancy between the insurance date and the incident, and said they’d be in touch.

A few days later, in the afternoon, I was summoned to the phone at college. It was Betty, my mother-in-law. The baby was coming. I was given permission to leave, and rushed up to Nottinghamshire. Steph was in the early stages of what would be a very long labour. It went on for the rest of that evening and night. The midwife, a small very capable looking middle-aged lady, had been alerted, and was calling in regularly. The contractions continued all the next day. I was doing the usual male thing: fluttering about ineffectually. Steph and Betty were quite calm. Steph’s dad Frank and brother Kevin were looking apprehensive. In the evening, the midwife said the final stage was starting. She asked me if I wanted to be there at the delivery. ‘I insist’, I told her grandly. She looked at me amusedly, as if thinking, ‘Silly arrogant young twit’.

I should say at this point that this was forty-five years ago, before the day of ultrasound scans. We had no idea what we would be getting. As the time approached, the midwife, Betty and I gathered around Steph’s bed. Poor girl, she looked absolutely drained. The midwife had been sounding Steph’s abdomen regularly and remarked that the baby seemed very active. The foetal heartbeat was changing position a lot. As the baby’s head came into view, the midwife inserted her hand to help it out. She looked at Betty and said, ‘The cord’s around the neck’. Being so young and naïve, I had no idea what that meant. Of course Betty knew exactly. She and the midwife locked eyes. There was a long pause. Then the midwife recovered herself and, quite unceremoniously it seemed, although perhaps she didn’t pulled the baby out in a single movement.

And there it was. A tiny, bloodied, amazing, beautiful little creature was suddenly in the world. It was a little girl. I barely noticed the fleshy rope wrapped tightly around the neck. The midwife quickly placed her stethoscope on the baby’s chest. Entranced, like an excited child I looked at poor exhausted Steph and blurted out, ‘Look what we’ve got!’ The midwife looked at me sadly and shook her head. Finally, I realised that something was wrong; probably very wrong. Steph was alarmed too. ‘Is it alright?’ she asked. ‘Yes,’ I tremblingly tried to reassure her, ‘Yes, it’s fine’.

But it wasn’t. I was very frightened now. The midwife hadn’t given up though. She tore the umbilical cord away and then picked up a dropper-bottle of heart stimulant from her kit. She tried undoing the top. It wouldn’t budge. She handed it to me to try. But I was now shaking so much I was completely butter-fingered. I couldn’t do it either. She snatched it back from me and tried again. And at last succeeded. She filled the dropper and, opening the baby’s mouth, placed a couple of drops inside. Almost instantly, the still little chest began to rise and fall. It was incredible. Then she picked up the baby and gave gentle mouth-to-mouth resuscitation. And then, amazingly, the little mite opened her mouth and feebly wailed hello to life. Truly, that good woman worked a miracle that night.

The midwife then busied herself doing all the things that midwives do: cutting the cord, cleaning the mouth, wrapping her up and giving Steph our tiny precious new human being to hold. I was sent downstairs, weak-kneed, to tell Frank and Kevin that all was well. Fearing that I might do something ridiculous like faint, Frank found a bottle of rum and gave me a big tot. I really don’t like spirits, but I drank it down. Then I returned to the bedroom. Jenny – she had our chosen name-if-a-girl now – was swaddled in the cot prepared earlier. The midwife was a little concerned about her breathing though: it was worryingly ragged and shallow. I was despatched downstairs again to telephone the family doctor. Inadequate young fool that I was, when I spoke to him (in those days you could actually call doctors out of hours) I failed to convey the fact that the midwife actually wanted him to call.

So we waited for him to come. Ten minutes, twenty minutes, thirty minutes passed and there was no sign of him. The midwife was getting more anxious. This time, Betty made a second call, spoke more sense than me and the doctor arrived within five minutes. He was an elderly man who’d been the family GP for years. He took a look at Jenny struggling for breath in her cot and calmly asked for some cold water. I was sent for some and this time got the mission right. I returned with a beaker of water, the doctor wetted his fingers, flicked the coldness on her face, and little Jenny, shocked, took a deep breath and howled lustily. That was all that was needed to get her breathing properly. That wise old man performed another small miracle.

Later, the midwife gone and everyone finally in bed, there was one final little alarm. Jenny had had her first feed and was tucked up in her cot, and began to hiccup. Worried, I rapped on Betty and Frank’s bedroom door. Instantly awake, Betty called, ‘What is it?’ I told her. She came and checked; told us not to worry. She was right; soon the hiccups stopped. Later again, me back in bed and both of us reassured, Steph sighed.

‘Aren’t we lucky?’

‘We certainly are’, I replied fervently, ‘We certainly are’.

The third great miracle was that Jenny had no residual brain damage at all. I don’t know how long her brain was deprived of oxygen during her turbulent entry into the world, but it clearly wasn’t long enough to matter. Mercifully, she developed into a perfectly healthy child.

Back in Leicester, after Steph’s recuperation followed by a trip to Stamford to show my excited mum her granddaughter, it was time for other realities. I was summoned to the magistrate’s court about the driving offence. I pleaded guilty with extenuating circumstances and collected, quite rightly, a fine and surcharge on the road tax. It had been a stupid and irresponsible thing to do, regardless of the worry about Steph.

At college, I was continuing my final thesis after the dramatic interruption. This was the one really nonsensical part of the course, I thought. We were not academics; we were training to do a practical, creative job. Having a theoretical, academic knowledge of some obscure aspect of typography would not make us better designers. But it had to be done: it was a component of the much-vaunted final diploma. The tutor in charge of this irrelevance was Tom Wesley’s assistant, Doug Martin. Tom was very much a practical, teach-by-example sort of tutor; he would circulate among us during the sessions, sometimes sitting down at our drawing boards and, saying very little, execute exquisitely lettered designs. Doug on the other hand was more cerebral. With his combed-back black hair, goatee beard and three-piece suits (worn continuously until becoming frayed and shabby, after which he’d buy a new one) he looked more like an eccentric psychologist from Prague than a designer. He used to say, and I thought it very true, that a designer was ‘a sort of intellectual’.

It was Doug who taught us the thinking, problem-solving aspect of design, so it fell to him to oversee our theses. At the beginning of the third year he had given us a pep talk about it, rattling off examples of subjects we could chose to go for. It was very difficult to decide. Ted chose Gothic lettering (as practised by the old monks), as he was very much into medievalism. I hadn’t the faintest idea what to do, and eventually, because I had to choose something, went for one of Doug’s examples: typographical research. It was just about the most difficult thing I could have chosen. It was the sort of subject you would expect professors of the psychology of perception, or something, to research, not a very average art student in a red brick college. Talk about being right outside my comfort zone – again.

It proved very difficult. Our thesis study periods were spent in the college library, which was very well stocked with all manner of books on art and technology subjects. These sessions were punctuated with personal tutorials by Doug. I don’t know how the others got on, but in my case he would waffle on and on, citing work done in the field, discussing it, suggesting lines of research I could follow, as I sat there helplessly trying to take it all in. Part of my thesis should consist, Doug said, of practical research. So, cribbing ideas from books in the library, I prepared various tests involving reading the printed word, to be participated in, I thought, by a willing public. But then came the really hard bit: the testing itself. I suppose it would have been easiest to enlist students from the college, except that (a) they were all too busy doing their own things and (b) they would probably not be representative of the general reading public. So I set out, with my clipboard, onto the streets of Leicester. At first I tried collaring passers by. But of course I probably looked like a market researcher, and as people approached they spotted me and suddenly did large detours, or crossed the street, or even suddenly remembered something they’d forgotten back where they’d just come from. Any that I did manage to approach would mutter something like ‘Sorry, in a hurry’ and rush straight on by. It was hopeless.

Then I tried a different tack: a captive public. I went into a launderette and approached a young woman waiting for her coloureds to wash. Sitting down beside her, I said I was a student doing some research and would she help me with a few little tests, please? She looked at me warily. Poor woman: she didn’t look terribly enthusiastic. I fished out my test cards and asked her to read them. She did so. The results were quite unsurprising: just what common sense would suggest As (as was the intention) the tests got progressively harder to read, my subject got more and more embarrassed, thinking I suppose that it was a test of her intelligence (although it really wasn’t). But she struggled gamely through it, bless her, until the test wording was quite indecipherable anyway, and I thanked her. I looked around for other participants. Most people were suddenly taking a great interest in the floor, or hurriedly emptying tumble dryers and departing. I approached another elderly lady and told her what I was about. ‘Oh no’, she said’, I can’t do that sort of thing’.

So there was a big lesson to be learned there: don’t embarrass your subjects, or they’ll never participate. The memory of that ‘research’ interlude isn’t a happy one. I think I had one more go at it, visiting places like parks or the bus station, but the results were no better. The finished thesis was just pathetic: it consisted of ideas opined by Doug that I hoped he’d forgotten were his, and a discussion of the difficulties of conducting research among the general public. Hardly ground breaking stuff. I don’t remember there being a single original thought of mine in it. The other parts of the final exam were much easier as they were practical design tests. The final component was an exhibition of our course work. The diplomas were judged by a panel of working designers. At the exhibition one of them, a fairly eminent book designer, actually complimented me on my thesis. He said he’d found it very interesting. He was surely only being polite.

Then came the nerve-wracking wait for results. On the day, we were assembled in the Head of Department’s office and given the results. Generally speaking the diplomas weren’t graded, except that one student got a distinction. Two students who weren’t expecting success, failed. Another, one of the foundation people whom we all thought was one of the most creative students, also failed. He was absolutely devastated, poor lad. To my intense relief (I really thought I’d fail on the miserable thesis) I got my diploma.

That left the matter of finding work. Megan, the girl student, and I went to Bristol clutching our portfolios for interview with a large printing firm. There were two jobs on offer. Curiously, we were interviewed alongside each other. We of course were full of ourselves as newly graduated students, but perhaps the interview procedure was a measure of how low-grade the jobs were and our interviewers’ attitude towards us. Neither of us got the jobs.

That left two other possibilities for me. The first was an interview with Penguin Books. I’ve often wondered what path my career would have followed if I’d started it there. The second option was quite different. A junior lecturer for our course had previously worked in an advertising agency in London. A few months earlier, perhaps tempted by an offer too good to resist, he’d returned to the agency. Now he was seeking an assistant, and he’d recommended that the agency recruit from a reputable labour pool: graduates from Leicester College of Art. So there it was. A job on a plate, like Steph’s had been. No need to apply for it: Brian (the lecturer) would endorse me. I don’t know why, but none of the other students was interested in it. But I was. Most definitely. I had a wife and child to support, and if it was a choice between a guaranteed job and one for which I had to apply and might not get, it was no contest.