It’s often said – by those people sensitive to such things anyway – that old buildings have ‘atmosphere.’ That they could tell a story or two. I’d certainly go along with that. Take churches. I’m not a religious believer, but I do find a tremendous, almost palpable ‘atmosphere,’ if you will, inside them. Old ones, that is, of medieval venerability, not your Victorian Gothic Revival nonsense. There’s a wonderful sense of peacefulness; quietude. Ancient sanctuary, I suppose.

The engendering of atmosphere is found in any old building. In Through These Doors author Dianne Condon-Boutier uses a French manor house as the setting for her story, and goes as far as to make the house itself the narrator of dramatic events therein during WW2 and then decades later.

And we aren’t necessarily talking about large buildings. Provided that they still possess a lot of original fabric – doors, windows, fireplaces and so on – humble ones can exude character and fire the imagination too. Sometimes there’s a deliciously creepy ghostliness, which even if you’re a scientific rationalist it’s fun to imagine.

Using a similar time split to Through These Doors, writer Debra Watkins bases her delightful ghost story Symphony of War partly on a small town cottage in Beccles, Suffolk. Here is my recent review of it:

Speaking as someone who spent many years renovating and living in old houses, this excellent debut novella from Debra Watkins really resonated with me. Clearly very well researched, it is full of fascinating period detail like, for example, the discovery of the old ‘dolly tub’ whose use (for laundering in pre-washing machine days) is explained by mum Sylvie to incredulous daughter Caroline. Details like that add charm and colour to this very readable book.

Speaking as someone who spent many years renovating and living in old houses, this excellent debut novella from Debra Watkins really resonated with me. Clearly very well researched, it is full of fascinating period detail like, for example, the discovery of the old ‘dolly tub’ whose use (for laundering in pre-washing machine days) is explained by mum Sylvie to incredulous daughter Caroline. Details like that add charm and colour to this very readable book.

Yes, old houses do have atmospheres, and Debra builds on that to great effect in her descriptions both of the cottage and the hotel, her mother’s workplace.

Symphony of War (an enticing title in itself) is well paced, beginning in slow-burn mode but gradually building, becoming ever creepier, to a searing, emotional yet satisfying climax. I can well imagine that the good townsfolk of Beccles in Suffolk, where this is set, particularly the older generation, would love this; it would be a lovely nostalgia-trip for them. It evokes that quintessential English county town beautifully and the characters are likeable and entirely plausible too.

I think another reviewer’s comparison with the work of Susan Hill is right on the money. I also agree that this small but beautifully formed little gem could have been longer.

But that gripe aside, very well done indeed Ms Watkins!

The restored dining room

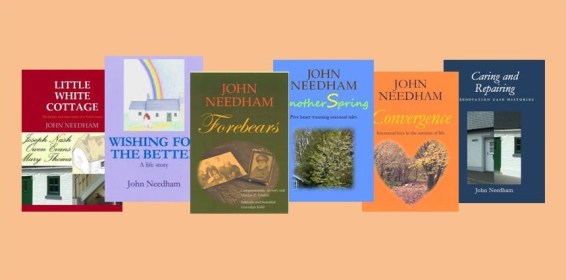

Here’s the original kitchen/dining room of a similar house I once owned and renovated near Birmingham in England. Fortunately, much original fabric had survived the depredations of modernisation, even the old black-lead cooking range. You may have seen the picture before, fairly recently. It appeared in an episode of my autobiography Wishing for the Better, which graced these digital pages a few weeks ago. If you’ve been following it, here’s chapter 12.

If you haven’t but would like to, starting from scratch, click on the cover image of the book at the bottom of the home page. It’ll take you to my post Keeping some kind of record, where it all began.

Wishing for the Better/12

To greatly misquote a famous (or infamous) Middle-Eastern tyrant, this is the mother of all B(C?)Ms. I’ve really done it this time. Recklessly burnt my proverbial boats again. I woke up this morning for the first time in the only place I now have to call home. A wooden shed. It’s weird, and a bit disconcerting, to put it mildly. At least when I started at Barratt’s Hill I was in a conventional house, albeit an extremely dilapidated one. Now all I have is the choice between a shed and a rotten hay-filled barn. And not only am I homeless, I’m jobless (again) too. Why do I do these things? Never mind. These temporary privations will all be worth it. I gaze through the shed window at the view. Beyond my fenced off garden area, a field slopes down to a copse of larches. Calves in the field, dimly curious about this new neighbour, gaze back. Beyond the copse there is a far-reaching panorama as the landscape rises and retreats into the distance and the pale green Llandinam Hills. It’s absolutely gorgeous.

The shed is reasonably habitable – at least, as liveable-in as it’ll ever be. During the week after officially moving, while I was living in temporary accommodation (oddly enough, a barn conversion) I had brought an electricity supply into the shed (it was already in the barn) and also water. Dai Lloyd, the farmer I’d bought the barn from, had brought a water pipe from the mains out on the road across the field to the barn, stopping it just inside my boundary. It had been relatively simple to extend it to the barn and insert a tee junction to take a branch to the shed. So now the shed had lighting, water and a means of water heating.

I had taken a scenic trip, thinking I was in paradise, through the mountains to a caravan equipment supplier in Aberystwyth to buy a bottled gas water heater. In my new nearest sizeable town, Newtown, I’d bought a plastic shower tray and curtain. Using painted hardboard, I’d improvised a crude cubicle. Now I had a perfectly adequate temporary dwelling, big enough to take my two-seater sofa, my double bed and the ablution arrangements. It was fine. A clever way of achieving interim accommodation, on site, I thought.

Rob arrived for work the following Monday morning and we got cracking. The very first, the most basic task, was to install a toilet, which would also involve, unlike Kingsnordley where it had been a simple cesspool, a proper modern septic tank. These are huge circular fibreglass containers, like the bottom end of a gigantic thermometer, which are buried in the ground. A man came with a JCB and excavated a huge hole and a trench back to the barn. I made my first purchase for the barn itself, a loo, and the pipes, inspection chambers and so on for connection to the tank. Clearing a space among the stored furniture and chattels, we installed the loo in what would become the bathroom, laid the pipes, chambers and buried the tank. Soon the system was working. It was a relief. As a man, and with it being in a remote spot, most of the time I could improvise, but I felt extremely silly using the ‘porta-potty’, also bought from the caravan place.

Job number two was to clear out the rotten hay, excavate and lay a damp proof membrane and concrete over all the floors. The plan then was to convert the smaller cart shed section of the barn, which would eventually contain two ground floor bedrooms with a master bedroom and bathroom above, into interim living space, with a bedroom (that would just about take the double bed if you breathed in to squeeze past it) in a lower back room and a temporary living room/kitchen in a lower front. That done, I’d be able to occupy at least part of the barn.

The first thing was to insert windows. I’d brought the ones I’d had made for Hilton: they would do nicely here. At the front it was simply a matter of making a suitable hole (although with random stone you tend to finish up having to make a much bigger one than you actually need and then rebuilding back) and inserting the the window and its lintel. The rear was slightly more complex. Having been a cart shed it was currently open, with a nice big oak lintel with incongruous brickwork above it. The brickwork was taken out and replaced with stones liberated from the front. Then a window was inserted with horizontal boards around it to close the opening.

By now the concrete was dry enough to be able to move all the stored stuff into the main barn, leaving us free to work on the top floor. We stripped off the old roof completely, leaving the ‘bathroom’ spectacularly exposed and needing shielding in the interests of modesty. Then we constructed a new roof for the cart shed end. In order to achieve sufficient headroom in the two-storeyed end of the barn I had planned large dormer-type structures, although they were only partially occupied by windows. The remainder was clad in the same slate we used for the roof.

We knocked openings through at two levels into the bedroom end and Rob, who was essentially a bricklayer, built the edges of them back tidily. I removed the corrugated iron sheeting from the front of the main barn, exposing the splendid oak posts that had almost certainly supported horizontal boards originally. They would be left showing inside. Supplementary softwood posts were added, leaving a large double door opening, and then windows and more horizontal boards were installed. It was shaping up nicely.

At this point Rob left for a while – not because he walked off the job: it was simply that I could now manage alone. I’d said at the outset that I’d employ him just in the early stages to help with work I couldn’t do single-handed. This was partly a matter of affordability and partly that I wanted to do as much as I could myself purely because that was the Grand Plan. All the same, I felt a little guilty dispensing with his services like that, although he told me he had other work lined up.

With the bedroom end weather-tight and dry, I could now move in. It wasn’t before time: it was late October and nights were getting distinctly chilly in the shed. Things were pretty basic. The front bedroom-to-be contained just the sofa, TV, improvised work surface and washing up bowl with cold tap over, plus the water heater brought in from the shed. The back bedroom held – only just – the bed. There was no way up to the embryonic bathroom except by ladder, or the external staircase. But compared with life in the shed, it was a definite improvement. Now I could complete the upstairs. I partitioned the master bedroom off from the bathroom and insulated and plaster-boarded the walls. A new floor was laid. Then I finished the bathroom, with plumbed-in basin and even a bath. A hot water cylinder was installed, with immersion heater, and at last there was full hot water on tap.

By now winter was breathing down my neck. There was the pressing need to close the enormous gap for the main doors. I’d given a lot of thought to this. Most barn conversions replace large door openings with patio doors that simply look like that. But I wanted to create the feeling of two large full height barn-like doors whilst at the same time letting in plenty of light. My solution was to make two doors of normal height, each of them four feet wide. They would be simply boarded in the traditional manner. The remaining wall above the doors would also be boarded in the same style, so that when the whole was painted it would look like a pair of very large doors. The right hand door would open inwards for access, but the other one would open outwards, like a big shutter. Here’s the clever bit: on the inside of the left hand door there’d be a large single-paned double glazed patio-style door, but fixed. So when the left hand door was open it would look like just that, but there’d actually be an ‘invisible’ window keeping howling gales at bay and letting in lots of light. Well I thought it was clever, anyway.

I made the doors, and then slightly regretted that Rob had left. He was a young, strong chap. They were incredibly heavy, and it took a lot of heaving and straining and temporarily resting them on blocks of just the right height before I had them hung. That’s one skill I’ve learned over the many years I’ve been doing this sort of work: how to devise aids to work single-handedly when there’s no one available to lend extra muscle or help hold things in place.

Then I had the enormous double glazed glass unit made. When it was fitted and the doors painted, the result was pretty much as I’d visualised. I was quite pleased.

In the summer of 1992 life took a bittersweet turn. Or, more precisely, a sweet turn that would later become bitter. Having got the barn reasonably, if only partially habitable, I decided to have another try at finding a lady friend. As usual, not having a social life and the opportunities to meet people in the ‘normal’ way, I tried the lonely-hearts route again. Trying to be rational about it (insofar as you can be rational about relationships) I placed an advert in a walking magazine. Surely that might produce someone like-minded, with a shared interest.

There was a reasonably good response. I wrote back to likely sounding people, able I suppose to paint a fairly intriguing picture of myself, doing what I was doing. One respondent sounded particularly interesting. About my age, she was a theatre wardrobe mistress and amateur water-colourist – clearly a fellow-creative person. There was also the love of landscape and walking in common. Divorced like me, she wrote a good letter and seemed to tick many boxes of similar outlook. I telephoned her and we spoke for ages. There seemed to be quite a rapport. We arranged to meet for a country walk in the Welsh borders, and it went swimmingly. We talked and talked, constantly finding new things to agree about. It was like it had been when Steph and I met our potential commune partners sixteen years earlier, the same sort of why-didn’t-we-meet-earlier? feeling. There was the same intellectual and emotional high.

We had another trait in common though: impetuosity. She had set out with every intention to go cautiously, and I suppose I was trying to, not very successfully, too. Fascinated by my descriptions of my project, she came to Penrorin the following weekend. She thought it was wonderful, and not at all put off by the improvised living arrangements. After that there was no stopping us. We quickly fell into a love affair. She came every weekend, and during the week we exchanged evening phone calls. I fell hook, line and sinker for her. Like a silly teenager, I composed embarrassingly flowery love letters. She brought out my self-expressiveness.

For all my intended rationality, there were the usual components in the relationship of romance, of hormones and simply of need. I ignored the fact that there were some, emerging, fundamental differences. I was a radical green socialist; Elizabeth was quite liberal in many ways but politically Conservative-supporting. I wasn’t too sure how we’d get on at a general election. Character-wise, I was an old softy and quite non-confrontational: she didn’t suffer fools gladly. Nonetheless, generally it was nice to have a caring partner in my life.

Things were happening in daughter Jenny’s life too. A few years earlier she’d finished an unsatisfactory relationship with an unsuitable young man. Then after some time alone she’d formed a new one with a much older man, someone my own age. She seemed quite happy with Robert, and he was certainly a nice man. I had few misgivings about the situation. Jenny was twenty-six after all and in charge of her own life. And I was hardly one to talk about age differences in relationships, anyway. In the March she’d announced that she was pregnant, and in late November she gave birth to my grandson, Fraser. (Robert was from Glasgow.) So life had a new dimension. He was a beautiful child and we visited Neyland regularly. I had to hand it to Elizabeth: she was really good with babies, far better than me.

Meanwhile, back at the barn, things were moving along. The time had come – I couldn’t put it off any longer – to re-roof the main body of the building. For some time it would have to be open to the elements. Fortunately there was nothing in there that could be spoiled by rain; the furniture and other stuff had been taken temporarily back into the upstairs bedroom. Rob came back to help. He soon had the old corrugated iron off, followed by the rafters. Knowing that some of the massive old purlins (the beams that run at right angles to, and support the rafters) were past it, I’d tracked down some replacement ones that were old but sound.

Now I had to hire a mobile crane, with operator. It would have been quite impossible for us to have manhandled them into place by hand. The crane spectacularly lifted the old purlins off and lowered them to the ground. If Fraser had been a couple of years older and present, he’d have loved it. Now all that was left of the old roof were the huge A-frame timbers that the purlins sat on. It all looked horribly broken and incomplete, as if a bomb had hit: there would be a lot of new building to do. And it would be mainly down to me. But I banished such negative thoughts. Soon the replacement purlins were in position, with the best of the old ones re-used in different positions, and the crane went home.

It was now relatively straightforward. Rob helped me fix new rafters, then felt with enough slate battens to hold it in place, then left me again. I could breathe a sigh of relief; now the place was reasonably weather-tight again. There had been a few fraught moments when it had rained and my temporary tarpaulin sheeting had filled with water instead of shedding it, and then without warning given way, drenching everything below. After watching Rob do the bedroom end and practising myself, I felt reasonably confident about doing the slating myself. Although it was quite a big roof for a novice. Well, I liked challenges. I found I could scramble quite confidently over the roof fixing the battens, without feeling unsafe. (Roofs with slate or tile on are a different matter though: on them my natural physical cowardice always wins out.) The slates went on surprisingly quickly, and it wasn’t many days before both slopes were finished. I admired my handiwork. Not a bad job. It was very satisfying.

I finished that phase of the project by painting facia and barge- boards grey, and the total result was quite good. Now I moved operations inside. The roof wasn’t actually finished yet. I attached the old oak rafters, after soaking them in preservative, to the undersides of the new ones, to give a total depth of six inches. Then I installed a thick layer of insulation between the rafters, topping it with plasterboard, leaving just the faces of the oak rafters showing. When the plasterboard was painted white, the high ceiling looked pleasingly ancient and authentic. The same process was applied to the inner front walls. The space between the posts was filled with insulation, then plasterboard nailed over it and the modern posts, leaving just the old ones visible. So the wall looked as if it was timber framed (which after all it was), with modern structures hidden.

In 1994 Elizabeth and I made a huge mistake. It would eventually prove emotionally costly for her and financially so for me. We began to co-habit full time. I’ve probably only myself to blame. Our relationship had cruised along pleasantly enough most of the time. The initial passion had subsided, but I supposed that was to be expected. Many – if not most – marriages become mundane after a while. Mine had after all (although I often wished after it was over that I’d tried harder with it). There were occasional irritations. Elizabeth was much more of a social animal than me. We went walking with her rambling club from Herefordshire, on prearranged days come rain or shine. I hated it when it was pouring with rain (didn’t see the point of that sort of masochism) and could take or leave the company. It made me realise that I’m more a solitary or possibly a very very small group person at heart. I’d found this at the commune. Her slightly overbearing tone grated sometimes. I think that my dreaminess and obtuseness irritated her a bit too. I didn’t warm to the fact that she hated dogs.

But generally, these were small things. Usually we didn’t argue, but there’d been a couple of serious ones that did make me wonder if we had a good basis for a relationship, and at one point I’d wanted to end things. But she became so upset that I capitulated and carried on, resolving to try harder. After all, I couldn’t expect constant bliss. We had been thinking about getting properly together for some time. She had a very small flat that would have to be sold first though. As far as her job was concerned, it was probably going to be axed anyway. She was confident of being able to find another one in Wales.

After being on the market for a long time, a buyer for her flat suddenly came along. This was the point at which, if I had serious doubts about us, I should have called a halt, however great the hurt. But I was soft. We could make it work. After all, we did still have much in common. I didn’t want to be so cruel. And in practical terms, getting together would be mutually beneficial. From her point of view, she’d have a much nicer home than she could otherwise have aspired to (notwithstanding that she’d have to rough it a bit sometimes). From mine, a wage earner in the equation would make my Grand Scheme more viable. We would be perfect partners.

Her sale went through smoothly, and soon she was with me. Having started her mortgage in very recent years, she’d made no profit to speak of and so brought no capital into my project, which was now our project. To be fair to her, having left her job she didn’t expect me to support her. She’d done moonlighting work for a nursing agency as a care assistant, and quickly found a similar agency in the local area. Then things looked up when a friend of hers decided to set up a costume hire agency in mid Wales, simply because that was where Elizabeth had moved to. She would be manager, earning a larger salary than she had before. Financially, things were really looking rosy.

I was now more than half way through the project, and we were looking at the market for possible next places. We looked at a couple of candidates: a chapel, and another barn. I wasn’t all that keen on doing another similar building and we ruled the barn out again. The chapel would have been quite nice, but then we discovered a much better one. It was in an absolutely gorgeous, picture postcard village a few miles away. The chapel itself was rather unusual. It was called Bont (Bridge in English) Schoolroom, and from the outside did look more like a nice elegant Regency school than a chapel. Internally though it was completely chapel-like, with pews and pulpit still in situ and a beautiful moulded wood ceiling.

It had tremendous potential, and was quite ridiculously cheap – £17,500. So it ticked all our boxes. It was a satellite building of a larger chapel in nearby Llanbrynmair village. We met one of the chapel elders from the mother chapel who was in charge of selling it. His name was John Morgan. A gentle soft-spoken man, he was the quintessential British gentleman, and farmed nearby. I was so taken with The Bont, as it was known, that I virtually said we’d have it there and then. Then, blushingly, I remembered myself and confessed that we were in no position to buy it yet. ‘Oh, that’s all right’, he said, ‘we’re in no hurry to sell it’. A sensitive man himself, he seemed quite touched by my enthusiasm about the place. As if to further demonstrate his gentlemanly credentials, he invited us back to his home to meet his family: his wife Freda (he called her ‘Freed’) who (by contrast with John, who looked nothing like a farmer) looked exactly like a farmer’s wife – plump and apple-cheeked – and son Bob, single, in his thirties and still living at home, who clearly had a generous helping of his mum’s genes. They were a lovely threesome. We became firm friends. Like the Normans whom I’d known years earlier in Bridgnorth Road, they were the sort of genuinely hospitable people you could drop in on at any time of the day or night. They would always make you feel welcome.

Needless to say, I started doodling plans for the conversion of The Bont. It would have been a terrible shame to make it two storeyed by inserting a floor into the space and completely altering the scale. Apart from anything else, the lovely ceiling would then become bedroom ceilings and be carved up by new walls. There must surely be a better way. There was! What if an opening was made in its exact centre (it was square)? Through this could go a spiral staircase into the roof space, which was steep enough and large enough to make bedrooms and a bathroom. Roof windows could go in the rear slope so as not to spoil the front. The main area of the chapel would stay unaltered as an open plan sitting and dining room, with the spiral staircase rising out of it and the ceiling still visible with its symmetry intact. A kitchen would be formed in the chapel foyer. Voila! It was designed.

But it was all very well daydreaming about the next project: there was the present one to finish first. I pressed on. The main body of the barn, which was divided by the posts and braces of the A-frames for the roof into three distinct ‘bays’, was planned as a single open area, to retain its barn-like character as much as possible. The bay nearest the bedrooms would be the kitchen area and include a staircase to the upper floor. The central one, into which the entrance door opened, would be for dining and the third one a sitting area. There would be a wooden screen of simple planks dividing part of the central bay from the kitchen, and fabric hangings partially dividing it from the sitting area. This meant there was a degree of compartmentalising into distinct areas by their use, whilst also retaining a generally open feeling.

I completed the floors. The central bay had an oak floor, with more of the oak planks used for the kitchen partition. The outer bays were finished with second hand red quarry tiles. For those floors we commissioned three beautiful hand-made traditional ‘rag’ rugs (made from scraps of old woollen or cotton clothing) in a nice red/brown/beige/tan colour way.

Two solid fuel stoves were installed. I put a huge black wood stove with moulded doors in the sitting room area, and in the kitchen the small Norwegian cooking stove brought from Kingsnordley, via Trelech, Bridgnorth Road, Hilton and Barratt’s Hill. This really would have to be its last resting place; I couldn’t keep carting it around with me. To complete the heating we had a conventional oil-fired boiler fitted, with traditionally styled central heating radiators in the dining and kitchen areas and ordinary slim- line ones in the bedrooms and bathroom. In spite of spending quite a lot of money one way and another on heating, this was one aspect of the project that I didn’t really get right.

It was probably a combination of things: in my desire to be as ‘authentic’ as possible I’d deliberately left the stone walls of the gable end and rear of the main area un-plastered, so there was no scope for insulating them (nowadays, rightly, insulation is a statutory requirement). They were simply cleaned up and pointed with lime mortar. They looked superb, but warm they were not. Secondly, with no upper floor in the main area and no internal walls it was a large volume of space to heat. I should probably have installed more radiators (and certainly should have sourced really dry wood to burn on the big stove), although that might simply have resulted in hothouse conditions up at the high ceiling with only moderate heat levels down below. I did try to incorporate as much ‘invisible’ insulation as possible though. The boarded main entrance door was double skinned, with insulation board sandwiched between, and I made the usual insulated shutters for the windows. Elizabeth decorated them with floral designs: they looked really nice.

Meanwhile we had been gradually bringing the garden into shape. It sloped quite steeply, so some terracing was needed. I built retaining walls-cum-rockeries with the rest of the liberated stone and created beds, we planted shrubs, trees, climbers, alpines, roses and perennials. It was all taking shape nicely.

Now came the part of the project I would be most pleased with – although it would give me one very bad moment. It was time to do away with our only means of getting upstairs (apart from the outside staircase), the ladder, and go up Wooden Hill in comfort. I built an oak staircase. It was simply styled, with plain square banister rails as befitted the simplicity of the building. On the other hand, it was not straightforward. It consisted of a main flight, then a square half-landing off which a shorter flight rose at right angles up to a second landing outside the opening through to the upper rooms. It wasn’t the first staircase I’d built (and the one at Bridgnorth Road hadn’t been easy either) but it was the first I’d made in hardwood that would be left unpainted. So it had to done very carefully, with no mistakes. There could be no rectifying with Polyfilla and then painting to hide a multitude of sins. I took it very slowly; doing many accurately scaled working drawings for each stage before I so much as lifted a saw. Apart from anything else, the wood was too expensive to waste if I made a mistake.

After many days of careful, breath-holding work, it neared completion. There was just the handrail for the main flight to drop into place, the joints being covered by newel post caps. I’d done the rails for the top landing without problem: it was easy to measure the lengths and add extra for tenons, to go into mortices in the newels. The one for the upper flight was slightly trickier as it was sloping, making the joints more complex, but it was possible to cut the rail oversize to begin with and then progressively nibble small pieces off until it fitted perfectly. The main rail had the same problem, plus the fact that, being longer; I couldn’t hold it in position to simultaneously check that both ends were fitting properly. I cut it to the length that seemed to be needed, plus a bit, cut the tenons and tried it for size. It dropped straight through between the newel posts. I’d made it too short! I could have cried. After all my painstakingly careful work, I’d fallen at the very last fence. It was desperate. I cursed and cursed myself for my lapse. And it wasn’t only my own work I’d spoiled.

Bob Morgan wasn’t just a friend; he was also an extremely useful man to know. As an extra money-earning supplement to farming he also did carpentry (and to a much higher standard than me). Again unlike me, he had a fully equipped workshop, and had moulded the components for my staircase that needed to be shaped. Like the handrails. As luck would have it, I had an extra piece of handrail-sized wood that was long enough to make another one. After a desperate please-help-me call to Bob, I rushed the spare piece to him and, smiling indulgently, he moulded another handrail. Bless him. Back home, I cut tenons in the new piece, leaving it well over-size, and over the course of several hours reduced it bit by careful bit, ever so slightly each time, until it fitted. There was now just the relatively easy bit of panelling in the undersides of the staircase with more oak boards to create cupboards, and it was finished.

I was really pleased with it. And at least the first handrail wasn’t wasted: it would come in for another staircase one day.

The project was drawing to a close. The main remaining job was finishing the kitchen. I’d built the carcasses for units and installed work surfaces. Now it was a matter of adding doors. I resisted the temptation to use any more oak: there was already plenty in the building, both old and new. Instead I went for simplicity again, with softwood panelled doors painted an understated straw colour. With so much genuine character intrinsic to the building, add-ons like the kitchen should, I felt, be as neutral as possible. As with all my projects, I was anxious to respect the integrity of the barn, and not impose my own personality on it too much, or be overly sophisticated. So the plastered wall surfaces were simply painted white. It enhanced the warmth of the oak.

The penultimate task was to complete the bathroom, keeping it simple again with neutrally painted wood panelling for the bath encasing and walls. Bob made us a nice traditional wooden gate to replace the rusty iron one that was a relic of agricultural days gone by, and finally I called up old typographical skills and painted a house sign. Well, barn sign.

During all this time, our friend John Morgan and his fellow Elders had kept the chapel available for us. Elizabeth was busy setting up her costume agency. The future, on the face of it, looked bright. At least, it should have been.

But things were not all they should have been on the home front. The irritations I’ve mentioned already were still there, and on my part at any rate were growing. I felt increasingly stressed. A little devil on my shoulder was slyly whispering that, really, I was a lone wolf. I’d lived alone – for most of the time – for eighteen years now. Although when Steph and I had first parted I couldn’t imagine being able to emotionally survive alone, I’d found with each successive year that bachelorhood was in fact survivable. Of course there were disadvantages in not having a loving and supportive partner, for obvious reasons, but there were plus points too, like total self-determination. In other words, the freedom to be selfish. I was torn between my growing uncertainty about Elizabeth and my conventional side that craved what most of us seek: the emotional security of a partnership.

I suppose that in this case there was the extra dimension that my lifestyle involved a big project. My previous three had been mine and mine alone. To some extent perhaps my other projects had been a substitute for a loving relationship, but I’d wishfully thought that I could have both. Now I did have both, but I was increasingly, ruefully, thinking that I was with the wrong person. That was the essence of it. It wasn’t a matter of who was right or wrong, simply a case of not really being right for each other. We were of the first generation to whom divorce was easily available. I hadn’t wanted my marriage to end, although it might well ultimately have done so, and Elizabeth had found hers unsatisfactory and ended it. Our attitudes were different from our parents’ generation, who were more accepting, probably mainly because they had no other option, of less than ideal relationships. At any rate, that was how I felt and I presumed she felt the same.

But, character differences apart, it was the project that would be the catalyst for us breaking up. I wished that she would do her costume thing and leave me to work on the project, which had begun as my own baby, in my own way. Like at the commune, I’d found it difficult to surrender autonomy. Perhaps I’m just naturally, in spite of my politics, not a co-operator. Of course the next place would be different: it would be joint from the outset, and she would be jointly funding the project and putting food on our table. But I wasn’t at all sure now that I wanted it, at least on a living together basis. So I was probably being ridiculously naïve when, knowing that ending the relationship would be hurtful, I suggested that we redefine it as a business partnership, with her ‘investing’ (in some ill-thought out way) in the chapel project.

Naturally, she was appalled and outraged by the suggestion, seeing it – not unreasonably – as simply a rejection, and a downgrading of our relationship. This is still quite painful to write about fifteen years later, and I’ll précis the long sorry saga. She left, and went to law to sue me for breach of contract, demanding either a significant percentage of the proceeds of the sale of the barn or a large lump sum (although moving to live with me had not financially disadvantaged her: in fact she was now better off. Neither had she contributed significantly except to support herself, until right at the end when the costume business began and the project was finished. Her upheaval was psychological and the loss was mainly emotional).

I had no option but to seek a solicitor’s advice myself. Had I known how expensive that would become, I would probably have capitulated in the first place. Naïvely again, I supposed that it would be a matter of negotiating a reasonable, mutually acceptable agreement between the two parties and their advisors. I thought that was what solicitors were for; I fully accepted that she felt aggrieved, and was ready to make a fair settlement. But it wasn’t like that at all. I was told that I had no option but to counter-sue to have a restriction that she’d placed on my selling Penrorin lifted. In other words, it might ultimately end up in court if not settled beforehand. As my solicitor cheerfully remarked as he checked his watch to see how many expensive minutes one of my sessions with him was running to, ‘The law can be a rough business’. How right he was: natural justice seemed to be for the birds.

And expensive it certainly was. To begin with, following his advice, I paid with an arm and leg for an opinion from a top flight London barrister who specialised, apparently, in property disputes. He charged over a thousand pounds for a ‘report’ that was largely a repetition back to me of a statement I’d lengthily written, with a few sentences at the end to the effect that her claim was hugely excessive. Then, after a date being set for the trial (it would be the proper thing, with a jury and everything, and all to decide what was basically a relationship breakdown with some property issues involved) there was the lengthy process of ‘evidence’ preparation (I keep putting words in quotes to show my contempt for the entire, expensive, nonsensical procedure. I can fully understand why lawyers are so well heeled). Here are two examples. It was thought necessary to employ a firm of surveyors to confirm that I had in fact done the project. Similarly, to prove the same thing, the solicitor took all my many hundreds of builders merchant’s invoices and expensively photocopied them all, charging me over two hundred pounds. I refrained from pointing out that the dispute was about how much she could reasonably claim in ‘damages’ for being rejected, not about the barn.

This went on from the spring of 1995 until the end of the year, with many (very expensive) letters being sent to me and more ridiculous evidence-of-nothing being prepared. The cost, paying up-front at hundreds of pounds per month, was becoming crippling. My solicitor never once questioned whether I was actually able to bear all this cost. In fact, as I was near the end of the project, funds were getting decidedly low. I really couldn’t afford to keep spending like this. And meanwhile, the date of the dreaded trial was looming ever closer. It was a horrible prospect. If only we could have settled things like reasonable human beings in the first place instead of this ghastly expensive power struggle. Finally, in the January of 1996, I had to conclude that I simply couldn’t carry on. In desperation I asked my solicitor to settle out of court and get me the best deal he could. He cautioned solemnly that I was in a very weak position. Elizabeth would have all the bargaining power. And so it would turn out. She wanted her original lump sum claim, plus her costs, plus interest because I hadn’t given in straight away. And there was the small matter of £7,000 I’d paid my solicitor for having failed to represent my interests. He told me, very magnanimously, that he would charge me nothing more for winding up the affair.

I now have to back-track nine months. Elizabeth had left and I was a free agent once more. But I didn’t have to be entirely alone. I’d grown up in a home where there was always a dog as part of the family. As a teenager I’d brought a dog of my own, Yogi (as in Bear) into the home. Later, married, we had the beautiful Sadie. But since 1977 I’d been dog-less (apart from a brief interlude at Hilton), mainly because of the impracticality of having a pet when I was rebuilding my life after the commune disaster. But now there was no reason why I shouldn’t have a canine companion.

I did have a doggy friend already. Rosie was a springer spaniel who lived at Penrorin House next to the barn. She spent her days shut in a yard with another dog (they had access to shelter though), most of the time eying me through the wire of her enclosure with those soulful hazel eyes that springers have. She sensed that I was a dog-friendly person. Before the arrival of Elizabeth I would often find myself wandering across the yard to talk to her. When her owner came home from work the dogs were let out, and Rosie was over to see me like a shot. She would never leave me, always taking a lively interest in what I was doing, and would stay with me until she was called indoors for the evening. She really adopted me. The attraction was mutual. I loved her, for her brown eyes, her long floppy ears, her curly head and her character: her tail was constantly wagging; she really seemed to enjoy life.

I just had to have one like her myself. My friends the Morgans egged me on. During an evening with them they scanned the pages of the Farmers’ Weekly for adverts of puppies for sale. There was a litter currently becoming available on a farm in Cheshire. The next day I rushed over to see them. They were gorgeous. But then, I think all baby animals are. Strictly speaking they were three or four days short of the ideal time for leaving their mum, but the owner accepted that I’d come a long way and returning in a few days would be a pain. And there was no way in which I could have returned home without one. I chose a pretty little bitch. I don’t know why I felt it had to be female. Just sentimentality I suppose.

So Bethan came into my life. I brought her home, quite unprepared for an infant. The breeder gave me a supply of puppy food to tide me over. Because I had no basket ready for her, I took her upstairs with me at bedtime and made a nest of laundry-awaiting clothes on the floor. I’m not the sort of person who can buy a little animal and then leave it shut downstairs alone in a strange environment, oblivious to its crying. The nest didn’t work. Naturally, she still found it all very alarming and cried anyway, so she had to be brought into my bed for comfort. She snuggled up to this suddenly much larger mum. I tried to spend that first night awake, because she had a tendency to fall off the edge of the bed with a disconcerting thump. The following morning the bed was covered in puddles and smelly little souvenirs, but I didn’t care.

Apart from the times when she assaulted me in play with her needle-sharp little teeth, and when later, swapping them for proper grown-up-dog teeth, she chewed things I would have preferred her not to, her puppyhood was a joy. It was a shame that she grew so quickly. I have had a dog ever since then; now I couldn’t imagine life without one.

With the departure of Elizabeth I’d lost my resident needlewoman (and she was very good one). But there was someone else more than willing to take on that mantle: daughter Jenny. She was fascinated by the barn project, and we had already commissioned her to make some very creative fabric hangings, instead of curtains, to cover narrow ventilation slits, now glazed, in the rear walls. Depicting themes of spring, summer and autumn, they were beautifully made collages of motifs fashioned from fabric interspersed with swatches of knitting. They were lovely.

Now she flourished. I’d found an old pitchfork head, and fitted onto a long wooden dowel it made a unique curtain pole for the large ‘patio’ window. She made a special curtain to go with it. Only having a two-seater sofa, bought for my first solo house, Bridgnorth Road, I was a bit lacking in sitting room furniture and couldn’t really afford more new seating to fill my quite large living space. Jenny came to my rescue. She and partner Robert had an old three-seater sofa, which she had made a set of loose covers for. It had become a bit surplus to their requirements, as they’d now acquired another one, also re-covered by her. She gave me the three-seater and offered to make another set of covers in my own fabric. So she was now doing her work all over again.

It was touchingly kind. She came to visit and we went to my local Laura Ashley shop in Newtown, where I chose and bought fabric. Not content with doing that, she also made patchwork scatter cushions from left over scraps. Now I have a smaller dwelling I have rather an embarrassment of seating, but I will never, ever part with Jenny’s sofa. Bless her heart.

Of course, in finishing with Elizabeth I’d also seriously worsened my financial position. There wouldn’t be her income now, or ever again. I’d been reasonably comfortably off during the project because I’d done well selling Barratt’s Hill. For the first – and last – time in my life I’d become, to my slight embarrassment, a capitalistic Investor, with money in unit trusts earning enough to pay income tax. That was now dwindling rapidly, and I wasn’t quite so confident of being able to sustain my chosen lifestyle in the future. Then brother Derek, with a throwaway remark, gave me an idea. Talking about the barn, he casually remarked that, with it’s fairly remote situation it would ideally suit someone like a writer. Really? That set the normally slowly revolving cogs in my brain spinning a little faster. What if . . . What if I could earn at least a small income (and I could live on comparatively little) from writing and superimpose it on the Grand Scheme? Combining two different activities, it would reduce the amount of time available for renovating, so it would lengthen the duration of each project. But that was no bad thing. It would in some ways be a reversion to my previous conventional life, but with the advantage that the normal money earning would be from something actively chosen, not something I’d been forced back to, and be on a properly freelance basis. Having the freedom of self-determination since leaving Cyril again was something I really cherished.

Yes, I know what you’re thinking. Here he goes again. Is this another B(C?)M? Well no, not really. It was, for once, quite a rational thought. At this time there were adverts in the media for correspondence writing schools, which claimed that it was quite possible, with training, to earn useful amounts of cash. I’d been reasonably good at writing at school, somewhat to Derek’s advantage. And I’d done a bit professionally, in copywriting for Cyril. Actually, I’d even started writing about this Penrorin segment of my life when I began the project, but dropped it as I got involved in the work. Perhaps I could make a go of it. It was worth a try.

So I enrolled with a correspondence school, and paid the course fee. It was certainly quite a comprehensive course, covering fiction, non-fiction, journalism and even things like playwriting. Advice was given about selling one’s work (one of the main planks was ‘write the things that editors want rather than what you want to do’, on the basis that they knew what their reading customers wanted to read), and encouraged students to begin trying to sell work as early as possible.

It was all very interesting, but I quickly came up against difficulties. Writing fiction was a lot harder than I’d imagined. And finding markets was harder still. The school wasn’t advocating anything as grandiose as novel writing, but the more modest goal of short story work. I saw the logic of that – learning to walk before you ran – but the problem was markets. Most stories were written for magazines, and most of them were the women’s publications, which mainly used romantic fiction. I sat and tried gallantly to concoct stories in that genre, but my heart wasn’t really in it. I was currently going through a bruising relationship break up and property dispute after all. I didn’t want to be writing about people falling blissfully in love. But I just couldn’t see any other markets open as far as fiction was concerned. I ruefully commented to my tutor that as far as magazine fiction was concerned, I was probably the wrong sex.

I got on a little better with non-fiction – things like magazine articles – and attracted fairly favourable comments. After some time still struggling with the fiction, I asked if I could concentrate only on articles. The college agreed and I was assigned a journalism tutor. There was still, though, the marketing problem. I could (theoretically anyway) now cast my net more widely, but it was easier said than done. There seemed to be two main difficulties: expertise and fees. Another of the school’s tenets was ‘write about what you know’. In other words, if you are an expert in a particular field, write about it because you will have something interesting/useful/entertaining to say, that editors can sell. Self-evidently obvious! There might be opportunities at the popular end of the market where it would be sufficient to invest just enough research in a subject to be able to produce a credible and reasonably intelligent-sounding piece without sounding an utter fool, but many of the magazines I looked at on newsagents’ shelves seemed to be contributed to by real experts.

And then there was the money aspect. The fees you could expect were directly related to the circulation of the magazine. The bigger the magazine, the more money they could pay contributors, ergo, the bigger the publication, the higher-flying their journalists and the more difficult it was to break into them. Conversely, it was quite easy to sell stuff to local magazines with small circulations, but they paid peanuts. I found I could easily get work accepted by a local mid Wales general interest magazine, but its fee for an article big enough to fill a page, and including a picture provided by yourself, was a paltry £20. Clearly, I would never earn anything like a reasonable living operating at that level.

But I persisted gamely, constantly looking along my bookshelves for inspiration for articles aimed at specific magazines. If an idea for a piece presented itself I would read the book, and any others I had on the same subject and, trying very hard not to blatantly plagiarise, write an article. Then, because I hadn’t even got a typewriter, let alone a computer, I’d pay to have it typed up. I’d send it to my tutor, who would often, kindly, make quite favourable comments. Then I’d submit it to the editor of the magazine I had in mind, and that would be the last I’d hear of it. Editors had quite a cavalier attitude to contributors, simply because they received so many submissions. The school stressed that you must make the first few sentences of your article eye-catching. If they weren’t, the editor wouldn’t even bother to finish reading and your lovingly crafted masterpiece would go straight in the bin.

After some weeks of this my tutor began to politely suggest that, although I was writing reasonably well, I simply wasn’t being diverse enough. I could have told him that, but I just couldn’t see a way out of my dilemma. I did have a few acceptances though: a little piece (which I was quite pleased with) about a journey over a mountain road for a fairly literary magazine that went out of business within a few issues of being launched; and another about a local secret lake, written in rather flowery prose, for which I earned the aforementioned peanuts. Then my first article that ran to two pages, about a place from my past: Bridgnorth. It was for a national ‘heritage’ magazine and the fee was quite reasonable. Note the similarity between these examples though: they’re all about landscape or (old) built environment. They’re not suggestive of a wide-ranging mind.

Then I discovered what would turn out to be a fairly regular employer: a dog magazine. It ran regular dog walk articles, wherein contributors wrote about walks they recommended. There wasn’t a great deal of general writing involved; they were more like guides with step-by-step directions around the walk. There was the added interest that you were expected to also provide pictures. And you also had to give map details, by drawing the route on a photocopy of an Ordnance Survey map. So although there wasn’t very much descriptive writing, there was quite a bit of work involved. There was also the time spent in doing the actual walk, taking notes and pictures as you went. So all told you could reckon on two days if it was some distance away: a day to do the walk and another to write it up, do the map and in my case initially, get it typed (later I would invest in a word processing typewriter).

Nevertheless, as I discovered when my first attempt, a walk with Bethan around a beautiful local reservoir, was accepted, the fee wasn’t too bad. And also, encouragingly, the magazine asked me if I had more of the same to sell. I hadn’t, but I could soon produce some! By now it was 1996, and I would go on to do more, in August, September and November. The earnings from writing were edging very slowly up, but there was still a long way to go before I could call them a proper income. If I could have found more regular employers like the dog magazine, I would have been well away.

Now I go back again to 1995 and the biggest event of all in the Penrorin period, one that dwarfs even the Elizabeth debacle. It was painful to write about that: this one is even more so. One evening Sarah telephoned. After chatting about various things, she paused awkwardly and asked if I knew about Jenny. No, I said, what about Jenny? Her silence continued. Alarmed now, I asked again. Reluctantly she told me: Jenny had been diagnosed with breast cancer. It was being regarded as urgent, and she was having a mastectomy in two days time. After Sarah had told me all she could, I rang Jenny. I berated her gently for not telling me before. Sorry, she said, she didn’t want to worry me.

It was a massive shock. Cancer was one of those subjects best ignored, only happening to the elderly or in other families. She seemed very stoical about it. When two days later I rang the hospital for news my call was put through to her. She’d had the operation and felt fine, she said calmly and cheerfully, as if talking about something trivial like a fracture. She was discharged a day later and I went to visit. Apart from a slight paleness, she looked very well. Then she began a course of follow-up chemotherapy, and of course felt rather less well because of the treatment. Later there was to be reconstructive plastic surgery. I telephoned frequently for updates. An unselfish girl, she seemed more concerned about my relatively unimportant problems with my dispute than her own troubles. I just wanted to discuss hers, but felt inhibited; I didn’t want behave in completely the wrong way and come across as the typical ineffectual, hand-wringing male. I wanted to give her my strength, but didn’t know how to do so.

Christmas came and she continued to be well. I knew much less about cancer then than recent events cause me to know now and my first anxiety subsided. She would be fine.

In the New Year my dispute came to its sorry end, and with the barn finished and looking really good thanks partly to Jenny’s help, I went on the market. The agent’s valuation was disappointing. I’d expected, hoped, that being a building of considerable character it might realise £100,000, or perhaps just under. He was less impressed with its charm though, feeling that a typical three bedroom detached (but surely it was more than that?) commanded about £75,000. Knowing that I would be deducting a hefty sum from my sale proceeds, I haggled to raise the asking price. The agent seemed rather dubious, but we agreed on £86,000. The housing market was not booming in the mid 90s, and there were few enquiries. Or perhaps I’d been too keen on authenticity rather than being canny about saleability. Whatever the reason, it was worrying – although not as much as the other underlying worry. I simply had to sell, for whatever I could get, to rid myself of the litigious albatross around my neck.

Then the worst thing happened. Jenny’s cancer returned. Perhaps it had never really been cleared up, as she had gone for a while undiagnosed, and by the time the tumour was discovered it was quite advanced. A scan showed secondary tumours in her liver and bones. She was referred to a Swansea hospital for regular radiotherapy, and I still hoped for the best. As I had done because of my mum years earlier, I considered moving to be much closer to her in Pembrokeshire when I sold. I had a weekend in Neyland and Steph, Jenny and I toured the agents and looked at a few places. We found nothing really suitable, and Jenny was exhausted by the walking around. But perhaps it was rather a futile – if well meant – gesture. Living closer wouldn’t really affect any outcome. If only it could. It would be quite a different situation if she were likely to become long-term disabled; then there would be a practical consideration.

Finally, in the July, I found a buyer for the barn. There was almost a choice of two. A couple came first, and seemed quite interested. They had quite a large family. Trying to anticipate any reservations they might have, I pointed out the possibility of inserting a second floor above the kitchen area to achieve another bedroom. They returned for another look with their family, and they all still appeared keen. But they seemed reluctant to commit to an offer. Then a man came alone. Presently living in the west Midlands, he had got a managerial job at Laura Ashley in nearby Carno, and he and his wife were looking for a second home in the area. He appeared interested, and he too returned with his wife for a second look. She also reacted positively, and the following day he made an offer. But was only £70,000. It wasn’t enough. On the other hand, in my unfavourable situation a low offer was better than none. My agent tried to raise him to somewhere in the upper £70,000s, but the most he said he could afford was £75,000. Reluctantly, I had to settle for that.

So now I had to find somewhere else, and quickly. As I’d increasingly found in England, the supply of places to do up was rapidly dwindling. Now there were few to be found in Wales too. I’d given up on thoughts of having the chapel now. It was cheap (although the price had now risen to £22,000 because extra garden land was available from the adjoining field), but I simply wouldn’t have the funds now to spend on another big project. The only other candidate was a tiny cottage in a small village called Llawryglyn, near Trefeglwys. Jenny wanted to see it, and Steph drove her up to see me for a weekend. It was a lovely drive along a single-track road through a sweet valley to Llawryglyn (‘Floor of the Valley’ in English). The cottage, built in the same sort of warm grey stone as the barn, was certainly diminutive. A semi, attached to a rather nondescript cement-rendered house, it consisted simply of a fair sized room with a much smaller one partitioned off at one end for a kitchen. The house had been a holiday let for many years and was astonishingly primitive. Kitchen fittings consisted of just an ancient sink unit, a tatty table and a few shelves. Upstairs there were two bedrooms but no bathroom. Any toilet must have been of the chemical variety and presumably housed in a lean-to outhouse. The cottage was very prettily situated beside a stream though. It still contained a few items of geriatric furniture and poor Jenny was glad to sit down. She still managed to comment, wanly, that it was a nice little cottage. What a sweet unselfish thing to say. I wished I could do it up and give it to her.

The following Monday I offered the asking price of £25,000, which was accepted. Now I knew where I was going I could do the sums. I’d had to accept £75,000 for the barn, which was barely £72,000 after costs. From that £23,000 would be deducted for Elizabeth, leaving just £49,000. £25,000 for the cottage deducted from that would bring the balance left to £24,000, off which to live and fund the next project. And there was not now a residue of £7,000 in the bank to put towards the new project because it had been wasted on futile legal costs. Putting it another way, the barn had cost £33,000 to buy and I’d spent a further £33,000 converting it. £66,000 deducted from £49,000 left minus £17,000, so I’d actually made a loss.

It was pretty galling. But never mind. I’d lost more than that before now, and after all it was only money. There was something far more important to worry about. There were no hitches with either the sale of Penrorin or the cottage, Henblas, and in the August I moved, again with Rob’s help. We used his Transit van, making many trips, as it was only a few miles between the barn and Llawryglyn. As usual, it was quite a shock moving down from a place I’d made into a beautiful dwelling of character into a grim, uncomfortable little hovel. But I wasn’t daunted by it; for me it was the normal way of things.

Now back to the important topic. Jenny was visibly declining. Her hair was growing back, thick, wavy and blond, but she was very poorly. In the August she went into hospital for palliative treatment to compensate for her failing liver. Steph and I visited her every day, taking little Fraser. Steph remarked to me how she seemed so withdrawn, as if she’d already left us, ‘gone far away into the silent land’ of Christina Rossetti’s poem. She was given infusions of various minerals and other things, and a blood transfusion. They did make her feel better. I remembered my poor old mum having a transfusion for her cancer too. People who aren’t involved in blood donation perhaps assume that blood is mainly used for accident victims or major operations, but it has many other uses, like saving sick babies’ lives or simply making suffering people feel a bit better. It brought it home to me again what a vital aspect of medicine this is, how it’s the one, and probably only, thing I do that’s entirely unselfish and positively good. When I began donating as a teenager it was in a spirit of Christian duty. Now there’s no deity involved; it’s a matter of Social duty. That’s what I feel anyway. Sorry to preach.

Back home, Jenny certainly looked a lot better. Her swollen abdomen had returned to normal and her eyes were less pained. Her appetite was better and she fancied fish and chips, so I went out and bought some for her. I would have bought her anything. Clinging to hope, I went into denial again. She really did seem better. Perhaps she would be all right. Perhaps if she had a regular toppings-up like she’d just had? Perhaps.

I returned the next weekend, after I’d moved to Henblas. She seemed about the same, perhaps looked a little more tired. My feelings had been shifting over the week. My denial was being displaced by acceptance. It was natural to grasp at straws, but one couldn’t ignore reality. I supposed that the strange calm I felt was nature’s psychological anaesthetic for coping with situations like this, or something. On the Monday morning, before leaving again, I looked into her bedroom. She hadn’t yet got up.

We are a notoriously undemonstrative family. I suppose I am so because I was brought up in a family that wasn’t comfortable showing affection. The only one who broke the rule, who was generous with hugs and in so many other ways, lay there pale in her bed. But I sat on the bed and took her hand. She smiled at me, serene and brave. She seemed to have reached acceptance too. ‘Perhaps I’ll see Grandma Needham’, she said. ‘Yes’, I said, choked, ‘I’m sure you will’.

I touched her pale cheek. ‘There’s one thing’, I said, ‘we do all love you’. ‘I love you too Daddy’, she said. Then she cried, and I cried, as I’m doing now.